The minister for trade’s response? “I sympathise with the fears which prompt such demands, but I do not think that it would be right for the [Labour] government to accept the logic which seeks to justify them.”

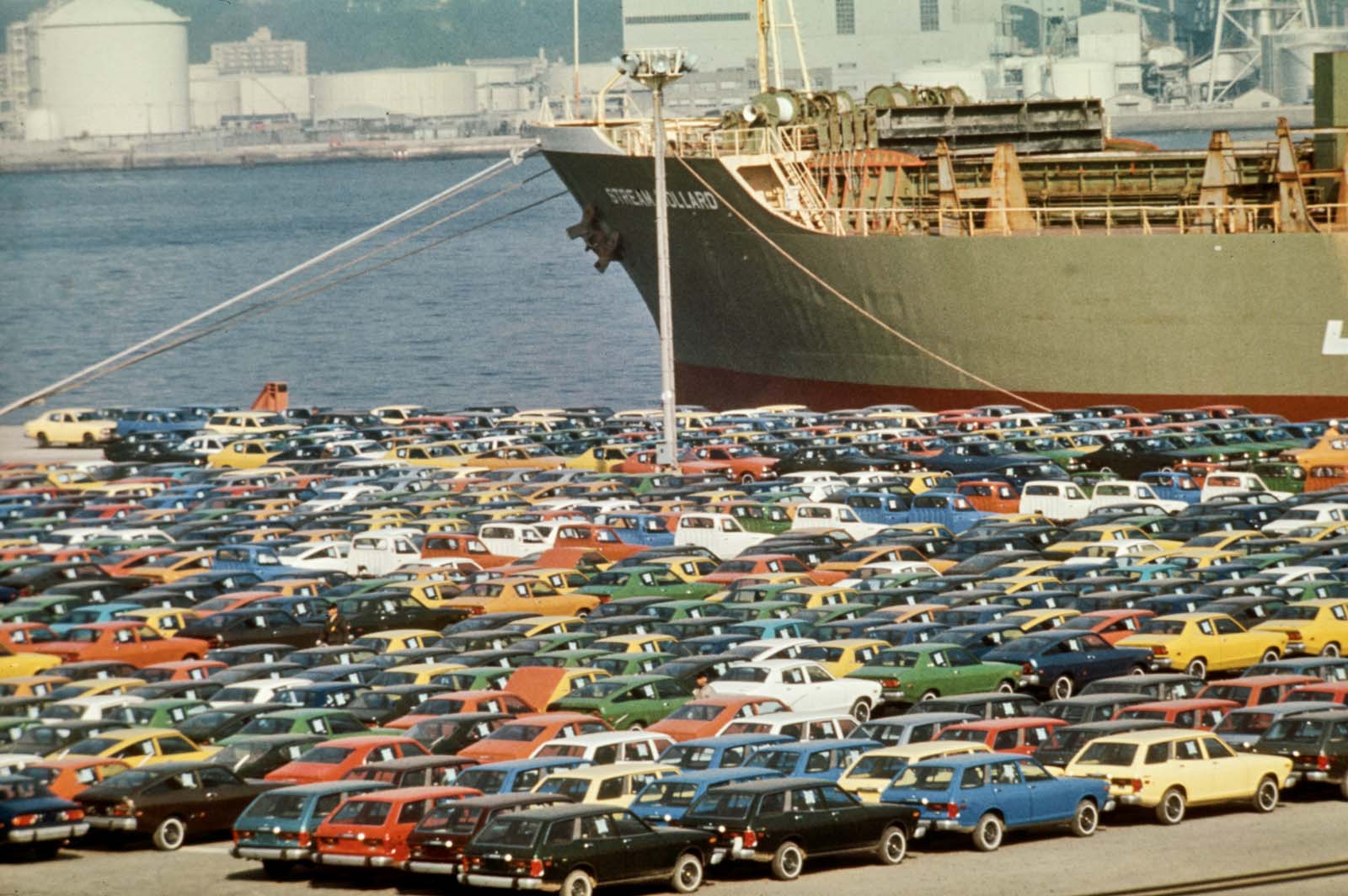

But that December, the SMMT met with its Japanese counterpart to make “its usual complaint” – and JAMA promised “the level of sales achieved in the latter part of 1975 would be continued for at least the first three months of 1976”, keeping its members’ share at about 10%. Why? We assume primarily because the SMMT threatened legal action under the Customs Duties (Dumping and Subsidies) Act 1969.

By April, the two trade bodies were arguing. The SMMT alleged Japanese firms weren’t honouring their ‘voluntary agreement’ – which JAMA vehemently denied, adding: “It appears the restraint expected of [us] simply means the substitution of [our] cars by other foreign cars.”

The informality of the 10% ‘rule’ created another headache in early 1977, when Subaru announced its intention to enter the UK: which of Datsun, Toyota, Mazda, Honda and Colt (Mitsubishi) would have to give up some sales to make space for it?

Toyota’s answer was Datsun, as it sold more than half of all Japanese cars here. “We are at the short end of the stick,” concurred Mitsubishi. Incredibly, Datsun UK responded by claiming that no such restriction had ever been agreed to anyway.

But it certainly had been, and JAMA renewed its vow many times, upholding the share limit all the way to the end of 1999 – by which time calamitous BL was long dead.