Can the brilliant new M2 CS hold its head up against two icons of BMW’s M car lineage?

The new BMW M2 CS is a special kind of fast BMW. Well, it certainly seems that way to me, if not quite to the other judges of our Britain’s Best Driver’s Car shootout.

Democracy can be cruel, as BBDC history has proven time and again for BMW M cars. A combination of ‘Cup’ tyres and changeable weather can be crueller still.

My suspicion is that if all five judges had spent as much time in the M2 CS as I did, driving it up to and back from the Lake District so many hundreds of miles in better conditions as well as bad ones, it would have ranked higher. Or, to put it another way, I think it deserves another chance at some glory. And this is it.

Today, the M2 CS meets a couple of cars that show exactly what it takes to earn a place among the M car immortals. In such company, we’ll find out just how special this car’s particular brand of ‘Competition Sport’ really is.

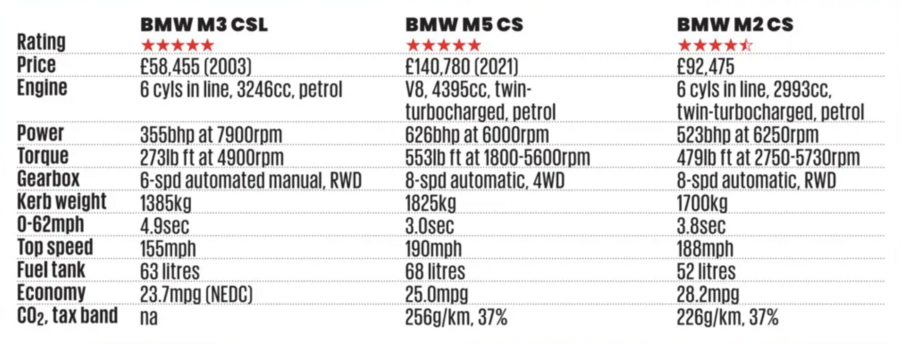

We’ve got all the light that an early winter’s day can provide and, in addition to the new M2, we’ve got a four-year-old ‘F90’ BMW M5 CS to take with us, plus a 22-year-old ‘E46’ BMW M3 CSL. This shouldn’t be your average Monday.

The M5 represents the last time BMW produced genuinely spectacular results with the CS suffix, and it’s the first — and as yet only — time it has been used on an M5. And the M3 CSL? Well, it would probably give both the original M1 and the ‘E9’ CSL ‘Batmobile’ a pretty stiff challenge for the title of most celebrated M car of all time.

If you happen to find £150,000 of used banknotes stuffed in your Christmas stocking this year, you could take your pick. That amount would get you a very nice M3 CSL, a mid-ranking M5 CS or a fully loaded, new M2 CS — with enough change to build a garage in which to keep it.

The newbie would be considerably the easiest of the three to come by. E46 CSLs typically only come onto the market in twos and threes; F90 CSs appear even more seldomly, which actually reflects their rarity.

UK registration data has it that there are fewer than 300 E46 CSLs left, after a supply peak of a little over 350 UK-registered examples a couple of years after the completion of the car’s 2003 production run. Not many, then. But there have never been more than 50 extra-special M5 CSs on the DVLA’s books. If you want hen’s-teeth-collectable, the bigger car is actually the more obvious place to seek it out.

What we’re surveying before us here is M division’s first experiment of the modern era into crash-diet engineering, alongside its very latest and what is perhaps its most deliciously ornate.

In that respect, I think the M5 gives the E46 a run for its money. The CSL’s lightweight composite front bumper looks like an experiment. There’s an almost basic, motorsport-level sense of lashed-up visual purpose about its naked carbonfibre front splitter vanes and that improvised-looking extra circular ram air intake.

The car has an aluminium bonnet, probably because carbonfibre composite tooling wasn’t up to making a panel like that in 2003; it has glassfibre composite bucket seats and it has steel brakes.

It was, though, the first BMW with a carbonfibre roof, which, together with the forged alloy wheels and lightweight glazing, meant it weighed 110kg less than a regular E46 M3 coupé: 1385kg in total.

The M5 CS’s weight-saving didn’t achieve as much. It was 70kg lighter than a regular M5 Competition, although it still weighed in at a whacking great 1940kg in full running order. But the crash-diet efforts are wonderful to admire here.

This car’s ‘gold-bronze’ forged wheels are utterly gorgeous, and the sculpted, naked carbonfibre underside of its vented bonnet is ready to take your breath away every time you lift it up.

The M2 CS has a carbonfibre roof too, not to mention that rather adorable CFRP ducktail bootlid, which so clearly apes the CSL’s rounder lightweight steel equivalent.

Gold-bronze forged wheels, together with the weight-saving in the cabin, bring it in some 30kg lighter than a regular M2 auto, at 1700kg on the button.

The CSL is a car from a different dimension built entirely for the wild, unfiltered rawness of its atmospheric six-cylinder engine, the sledgehammer savagery of its automated manual gearbox and the connected feel of its drum-tight ride.

The M5 CS, meanwhile, does feel studiously modern, yet it has damping and wheel control that seems almost supernatural for something of its size and weight. Thanks to that free-revving 626bhp V8 and fully switchable four-wheel drive, it also has a character that can swing from assured ‘bahn-storming sophisticate to tyre-bonfiring, hot-rod hooligan at the press of a button.

Its dynamic range is genuinely staggering, and its capacity to inspire confidence is absolutely unmatched by any super-saloon in this tester’s experience.

No modern M car snarls and thrashes quite like an E46 CSL. It had BMW’s much-loved ‘S54’ 3.2-litre straight six in its very rarest, fiercest road-legal form.

When you unleash it, there isn’t Herculean poke, but the CSL just sounds — and indeed acts — so damn fast. Beyond 6000rpm it’s loosening your dental fillings and fizzing through your elbows. The M2’s stiffened engine mounts give it a suggestion of the CSL’s outright rawness, but it really is only a hint. It’s enough to lift it, though, to take it out of the realm of the ordinary and make you feel better connected to it.

The tautness of the M2 CS’s ride is comparable to the CSL’s. Ultimately, the E46 feels firmer, shorter and leaner over a challenging road, but the CS carries its additional bulk and weight rather well. There’s an unexpected sleepiness of off-centre steering response to the CSL compared to today’s darty and agile performance cars, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t wonderful precision and balance.

It guides you towards the apex, giving you supreme confidence to attack as hard as you dare. Get brave and the CSL responds with amazing progressiveness and delicacy. The harder you drive it, the more polished it feels.

In contrast to the CSL, the M5 CS feels hilariously over-endowed. Stick it in rear-drive, DSC-off mode and it will smear its Pirelli Corsas into a gloriously benign slide. Leave it in four-wheel-drive mode and you can just enjoy the tactility, accuracy and positivity of the steering instead.

And the M2 CS? It’s got enough of the M5’s outright grunt and rampant handling adjustability to make it feel fast and vivacious, and it comes in a package closer to the CSL’s for compactness and wieldiness. Genuinely, it’s at least close to a best-of-both-worlds situation.

Verdict

1st: BMW M3 CSL The CSL remains the high-water mark in its exalted performance car lineage for spine-tingling rawness, drama and excitement. Vivid and wild yet brilliantly polished on the limit.

2nd: BMW M5 CS Perhaps the best M5 there has ever been; quite possibly the best super-saloon of all. Does it all, from extravagant rear-drive hooliganism to tactile feel.

3rd: BMW M2 CS Falls slightly short of the big guns for combustive presence and dynamic star quality, but for a brand-new baby M car at a five-figure price, it’s very impressive indeed.

Memories of the CSL:

Stunt driver and friend of Autocar Mauro Calo, who drove on our test, was one of the first people to drive an E46 CSL on UK roads: it was he who got the job of driving a left-hand-drive press car over to Autocar’s London offices, 22 years ago, for our very first report.

“I had done one European driving job for Autocar at the time,” says Calo, “and just as I’d finished and road test editor Ben Oliver was thanking me for doing it, he asked me if I could do another the week after.

“I got the last flight to Munich one weekday evening, then a taxi from the airport to Garching to collect the car. I drove it back to the UK through the night, stopping only to fuel it and to catch the first ferry from Calais.

“I couldn’t believe my luck. It felt like such a special car, and I was driving it on incredible roads. I remember leaving the autobahn slip road at Munich and merging behind an Aston Martin DB9, which at the time was still a very new car itself. The two of us chased each other down this derestricted stretch of autobahn, way beyond 100mph, for mile after mile.

“My first rest was on the ferry from Calais, really; I remember handing the car over to the road test team at Autocar’s Teddington offices mid-morning. It was the one used in David Vivian’s August first drive report (Autocar, 12 August 2003), and the performance numbers were done at Millbrook. The full road test that appeared a few weeks later was done on a right-hand-drive car, though.