Written by and Photos by Alison DeLapp. Posted in Rides

By the time I arrived in Bolivia, I didn’t know which was in worse shape—my body or my bike. Beyond the common travelers’ ailments, the fan had stopped working on my KLR685, and an infection had reached my kidneys. We both ran a fever as we limped around La Paz looking for a cure.

I had searched all over the tangled city, frustrated at being turned away, or outright ignored… left wondering if it was because I was American or a woman… or both. It wasn’t my lack of Spanish; I had enough skills to hold a conversation. I tried checking with the motorcycle mechanic at the police station, where they rode newer KLRs, in hopes a spare part might be my ticket out of this country.

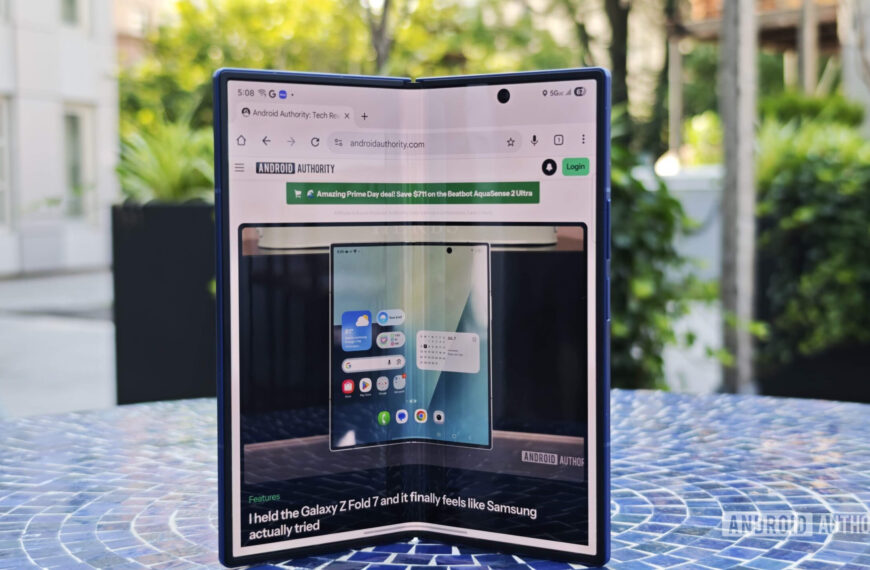

The muddy road out of Bolivia was the longest, not in miles, but in strength and patience.

The muddy road out of Bolivia was the longest, not in miles, but in strength and patience.

Alas, no, but I eventually found a man who would talk with me, even though he barely believed that I was riding by myself, and was even less convinced that I had any mecánica skills, or knew what was wrong with the bike. Finally, he understood that I didn’t need someone to look at my motorcycle, just someone to fix the part I had in my hand. He agreed to take the fan motor to the right guy because, for some unknown cultural reason, I wasn’t allowed to do so.

After three days of “Que estará listo en la mañana (it will be ready in the morning),” I anxiously walked back with the mended motor to the courtyard of the hostel where I was staying. While waiting, I’d flushed the radiator with fresh green blood (wishing I could do the same with my kidneys), replaced its oil, and lubricated its joints.

All it needed now was the reinstallation of its fan to get us back on the road. The cure for my motorcycle had been relatively simple, but my body was another story. Although the chills and fever had subsided, the pain had not—I ached. So, I drank a cocktail of antibiotics, apple cider vinegar and water, hoping to flush this ailment through my body. At this point, all I wanted was to leave Bolivia.

The next day, possibly against better judgment, I packed and departed with a sore lower back, making my way out of the maze that is La Paz. Midway through a long day’s ride, I passed the festivities brewing in Oruro, where brightly dressed marching bands gathered.

At the largest celebration of Carnaval in Bolivia, sequins and beer cans sparkled in the mid-day sun as they prepared for La Diablada (the Dance of the Devil). I watched the entrancing parade on a big screen at a pizzeria that night, about 200 miles away; that was close enough for me.

The next morning, I reunited with Deb, an Australian and fellow solo female rider, and her BMW F650GS . Being one of the highest cities in the world at 13,420 feet, Potosi took our breath away. But, as my body hadn’t fully recovered, we delayed departure one more day before heading south toward the town of Uyuni, knowing it would be healthier at the lower elevation.

For some reason I failed to stop for gas in Potosi. I’d been unlucky in the bigger cities with fuel purchases, sometimes having to stop at as many as three stations before one would sell any. A foreigner, on a foreign motorcycle with a foreign plate meant filling out all kinds of paperwork to appease the Bolivian government bureaucrats.

Hence, the phrase “No factura (no bill)”—meaning either that they didn’t have fuel, or didn’t want to sell it to me because it was too much bother. When I did find a willing station, there would inevitably be a sign that read: “$3 bolivianos for locals, and $b9 for extranjeros (foreigners).” Fine, take my money, but get me out of here!

So, as my miles increased and the fuel decreased, I crossed my fingers that the small towns ahead would have a tienda (store) to purchase a pre-measured pitcher of gasoline from limited reserves. The octane was never certain; sometimes as low as 81, and here, on a rural highway, I was happy to find any fuel at all.

As I exited the main highway onto a dirt road that led into town, I was thankful to have my face shield down. I learned the hard way that the children who stood along the side of the roads, often with water balloons and long-range water guns, had good aim.

Under the guise of Carnaval celebrations, they squirted anyone who passed. But, this time it was not water… it was a rock that hit my helmet square in the face as the child yelled, “Turista!”

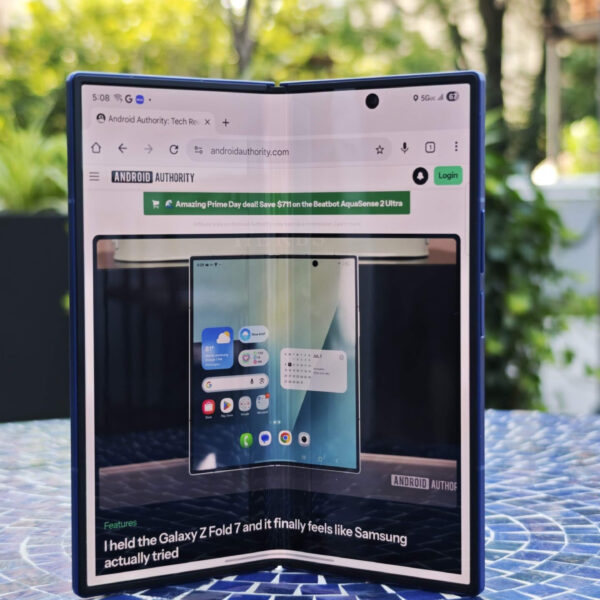

Carnival chased me all the way to behind the walls of the hostel in Uyuni.

Carnival chased me all the way to behind the walls of the hostel in Uyuni.

I pulled in front of the adobe brick building and bought ten liters, for a negotiated $b60, from an old man through a half open door. As I poured the contents of the plastic jug into the tank, I watched a woman smile at the drunken two-man marching band wandering around the square; merriment was everywhere. After the brief break, I hopped back on my KLR and speculated on whether it was going to get better or worse in the miles ahead.

There was freshly laid pavement connecting Potosi and Uyuni, with ample curves carving their way through a magnificently layered landscape. The blacktop and multi-colored terrain ended in the town of Uyuni, where rough dirt roads connected the sun-bleached buildings.

Layers of silt and sand kicked up by 4×4 tour vehicles seemed to cover everything. In a quest for a hostel with a courtyard to securely park the bikes, I reunited with another Aussie female rider I had met in Mexico, who was now two-up on a KLR, along with a couple on a KTM.

Wanting to get the best photos the sky would provide, we decided to visit the Salar de Uyuni for sunset. This was our one chance since none of us planned to stay another day. The 25 kilometer ride to the entrance was a bumpy one, and the unpaved ripio rattled bones, as well as the bolts on our bikes.

After parking our motorcycles for a few shots, we rode to another location just as the setting sun lit up the sky, providing a magnificent backdrop to work within. Then, as the light of the day extinguished, it was time to go.

The next morning we got off to a late start with the words of the hostel lady looming in our ears, “That’s a good road, as long as it’s not raining.” So, we took our chances, but racing against darkening skies we knew it was not a matter of if, but when, the black clouds would open with rain.

Dozens of Toyota Landcruisers, filled with tourists, kept the clay roads compacted. When dry, the road was comfortable for cruising at speeds of 55 mph. But, as rain fell, minor dips in the road filled with water, creating muddy pockets. The tour guides didn’t allow any extra room for our big foreign bikes, and with Jackson Pollock-like precision, one SUV even maneuvered toward potholes to intentionally splash burnt-red water over our bikes.

Washing off the salt of the Salar was futile as I’d be covered in mud in only a few hours later.

Washing off the salt of the Salar was futile as I’d be covered in mud in only a few hours later.

As the rain wasn’t heavy enough to wash the grime off my face shield, I tried to wipe the dirt away with my glove… but pounds of layered mud seemed to accumulate and stuck to my suit as well.

Reaching San Cristobal, which is more of a mining project than a town, we decided to stay for the night at the only hotel in town, not caring that the electricity was out, or that there were barely enough hot water showers. We would wait, and hope for sun in the morning.

While discussing the following day’s plans we realized our intentions of riding through the Eduardo Abaroa Andean Fauna National Reserve to San Pedro de Atacama, Chile, were unreachable. I’d heard of nothing but mile after mile of stunning rock formations and wildlife along the road to Laguna Verde and Laguna Colorada.

But, given our broken bikes and bodies, the excursion would have to wait for another day. That view came with the cost of treacherous terrain, and we were not up for the task of picking up our overloaded bikes time and time again. Instead, we chose to cross into Chile at Ollague via the easy road.

We carried the extra weight of drying red clay along with our already overloaded motorcycles.

We carried the extra weight of drying red clay along with our already overloaded motorcycles.

As light broke over the horizon that morning, we jumped for joy at the sight of blue skies interrupted with white clouds. Our wheels navigated by sunshine through a topography that lived up to the reputation of Bolivia as a place worth visiting. Even if it was not the Eduardo Reserve, we still basked in Bolivia’s brilliance.