Published in: Rides

Most riders take a positivist, mechanical, factual approach to riding. Bikes are machines, reducible to assorted piles of steel, nuts, bolts, springs, levers, reservoirs, fuses, wires, and molded plastic. Every observable phenomenon can be traced to the interactions of these parts and materials. But I take a fabulist, metaphorical, mystical view of riding. Motorcycles are miracles (or curses). I honor my vehicle, of course, by maintaining the chain tension and cleanliness, by changing the oil and greasing pivot points, as any supplicant attends to a shrine, but I don’t pretend to understand the transubstantiation of riding, in which my spirit seems to rise out of my body, which itself is flying above the ground.

Which is why, on my first morning in the Sierra Madre Oriental Mountains of Northeast Mexico, as the rain poured down in the Hotel Magdalena parking lot, the empty oil sight-glass on my V-Strom might as well have been the sun eclipsed by a cloud of locusts.

I thought I had fixed that drip with a new crush washer and some Teflon tape; it had seemed snug on the ride down, but now it appeared to have a slow bleed that was likely to seize up my bike at the most dangerous and cartel-haunted mountain pass. Since it was raining and everything in the tilting parking lot was wet, greasy and dirty, it was hard to tell for sure. My fellow riders—positivists to a man—appeared and explained through a tedious accretion of physical details (unlevel ground, cold engine, etc.) that the bike would probably be fine. Yet I could hear in that “probably” a note of doubt, and when we got to a gas station on flat ground 10 minutes later, only the thinnest skein of oil had appeared in the window. I was faced with a decision: ride and pray or wait and fiddle. I decided to ride.

Outside of Galeana, we snaked through a mountain pass, then turned south at the town of Iturbide onto a dirt road. The rain eased off and we bumped along under thick, dripping foliage as we contoured a narrow river. I was feeling uneasy, the overcast and unresolved weather mirroring my warring sense of hope and dread as I tried to concentrate on the rutted road and avoid thinking about oil hemorrhage.

At the town of Cuevas we made a river crossing near some bridgeless piles and long-dormant construction vehicles, then motored through hardscrabble ranch and farmlands to Camarones, a tiny town amidst the yuccas and prickly pears, low scrub pine and pacingo trees. The town was shuttered and still, but a radio was playing somewhere, a skittish mutt padded past us, and eventually a friendly campesino greeted us and gave us directions to the hamlet of La Luz. I put my bike on the center stand and checked the sight-glass, that stained glass portal into the Suzuki’s soul. And lo, I saw the honeyed, heavenly light of Castrol 10w-40. It was ¾ full. It felt like a miracle. The seal was good after all.

This was my second motorcycle trip to the Sierra Madre Oriental Mountains of Nuevo Leon, Mexico. On my first, I’d found that if one could get past the rumors about Mexico—gas shortages, cartel shoot-outs, heads made into soccer balls, etc., a landscape of miraculous beauty awaited: rocky two-tracks, towering waterfalls, cobblestone roads through ghostly mining towns. An ADV paradise. Any wounds a rider gets in northeastern Mexico will most likely be self-inflicted—the product of too much adrenaline twisting the throttle hand.

And so it was on this day, which took us on a beautiful, isolated loop, crisscrossing a stream multiple times, up onto bluffs overlooking a valley, through a tiny cluster of homes. Avoiding feckless goats, suicidal piglets, and one maladjusted bull, we skidded and splashed our way back to the river crossing at Cuevas, then to the blacktop. It rained again, then it poured, then in the high pass to Galeana it hailed. My nominally waterproof riding gear was soaked through. At one point I adjusted my stance and it felt like I’d dipped my nuts into ice water. I was soaked, shivering, but elated when we arrived back at the Hotel Magdalena in Galeana. Liquid gold had refilled my window.

The next day was overcast but the rain held off and we tried the “Gold Standard” route to Mesa Del Oso, from rider Rich Gibbens’ excellent guide of the area. Javier, our kindly doorman at the Hotel Magdalena, had warned us that the jeep road to Mesa del Oso was so steep a motorcycle would inevitably flip over backwards and crush its rider. He was sure of it. An experienced Texan rider had told me not to attempt the route if it was wet. Which it was. But we went anyway.

The route took us to Rayones, then Casillas, then onto a muddy two-track along the Rio Pilon, a lucid and fast-moving stream. Soon we climbed into a series of exposed, rocky switchbacks, at times brain-rattlingly bumpy and at times cinder-like and slick as butter, all on a steep pitch. A few wet, scabbed sections of striated concrete were almost worse than the dirt. We wrestled our bikes up the incline, pausing occasionally to rest, piss, and say, “Well, that was probably the worst of it,” only to find that it got tougher around the next corner. Clouds thickened and rain was imminent. I didn’t want to say anything, but I wasn’t sure I could go much further on my Strom.

Suddenly we emerged over a rocky shoulder, past a rugged little farmstead with scrawny livestock. The road flattened out, and—perfectly timed—we ascended through the cloud cover and into a bright day. We found ourselves in the Cumbres de Monterrey National Park, a Mexican Switzerland of towering peaks, tall pines and log cabins. We’d flogged our bikes and taxed our bodies, but we’d pierced the clouds and made it to Mesa del Oso—and that was only the first half of a ride that guided us through slot canyons and curvaceous paved roads, past cascading waterfalls and roadside shrines, up a second mountain pass, and deposited us giddy and exhausted at the Magdalena at dusk. The rain had held off and we hadn’t flipped our bikes over backwards. We hadn’t even dropped one sideways. That felt like Miracle No. 2. And the mead flowed that night.

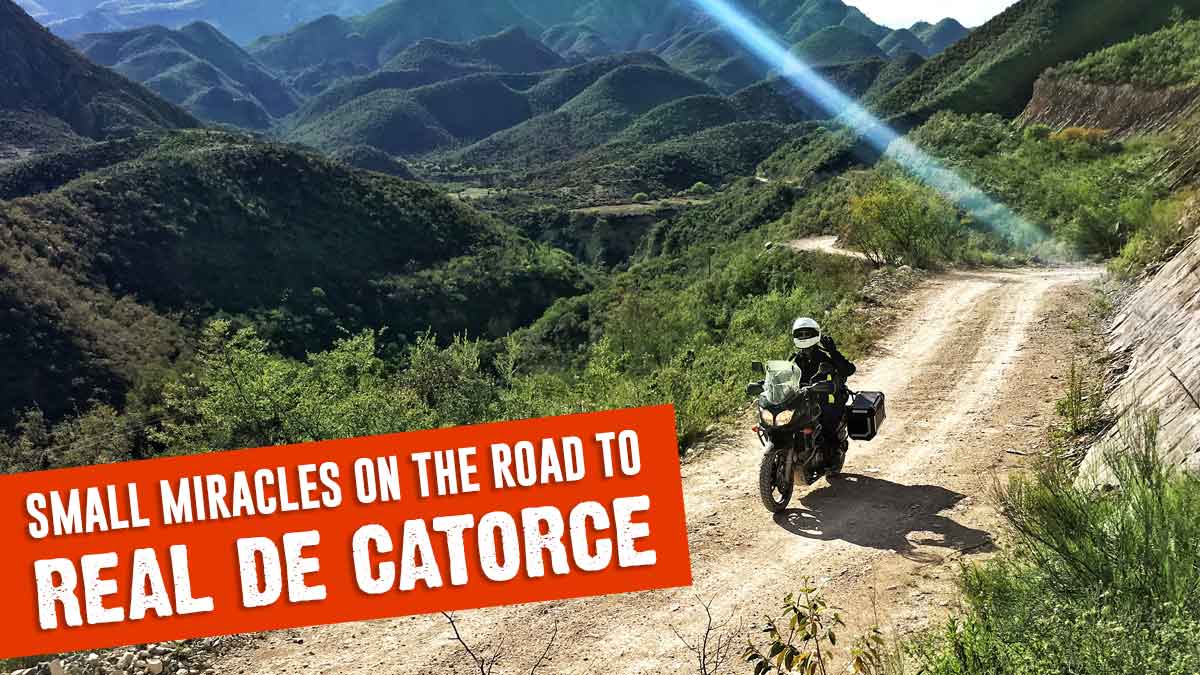

The next day we rode south out of Galeana to the town of Real De Catorce in San Luis Potosi, with a brief out-and-back detour toward a place called El Alamar. We had no idea which of the unsigned, twisting dirt roads led from Pablillo to El Alamar until a friendly, courteous older man with glittering dental work and a cowboy hat appeared. He led the way to the turn-off on his squeaking bicycle, our collective 3700ccs of motorcycle muscle prowling along in first gear behind him like obedient lions following a house cat. The weather was clear and sunny. Eventually we took off on a spectacular mountain road that folded gently over itself like poured batter until it stretched out along a ridge line with wide vistas opening to the north, branches and long hanging vines tunneling overhead, my loaded V-Strom rattling along the sun-dappled road like typebars on a platen.

By late afternoon we had traveled south across the Central Mexico Plateau, back up into the mountains of San Luis Potosi, and we reached the famed Ogarrio Tunnel outside the historic mining town of Real de Catorce. It was our last destination before the road home. The Ogarrio Tunnel was built for ore carts and retains the look of a horizontal mineshaft. Riding it is like traveling through a time portal; the amber lights of the ceiling shoot past overhead, periodically illuminating the battered stone walls and rough-hewn wood support beams and miners’ shrines. Sealed in a sonic envelope of muffled engine reverb, you cruise through the dark until a pupil of burning white light ahead of you widens and then you’re cast out into a dusty market area and the engine sounds scatter outward and you find yourself on narrow cobblestone streets hemmed in by steep, rocky hillsides with crumbling 200-year old stone buildings. It feels like you have arrived not only in a different place but also in a different time.

Real de Catorce was founded in 1779 among silver-veined mountains, and the mines brought wealth and elegance—theaters, grand hotels, salons, newspapers, brothels, a granary, a mint, and a neo-classical Catholic church worthy of a major city—but falling silver prices, political turmoil, and the Mexican Revolution made it nearly a ghost town by the early 1900s. The town has reimagined itself since. It’s the site of a sacred pilgrimage of the Huichol people of the Sierra Madres, who harvest peyote from the surrounding desert, as well as devout Catholics who honor Saint Francis Assisi in a fall festival, and international travelers looking for a spiritual escape in this high-desert, Sergio-Leone-meets-Carlos-Castaneda landscape.

We spent the next full day—our last before we returned—off the bikes, hiking up to somnolent ghost towns above Real, then perusing the cultural center housed in the old mint, where daguerreotypes of gaunt miners and stern silver barons battle for space with post-modern paintings and peyote exhibits. At the Church of the Immaculate Conception, I saw the famed and historical retablos: folk art visions of miracles hand-painted on square tin plates. There were thousands of them, some hundreds of years old. Each retablo told a story of Saint Francis’ intervention: the survival of a stabbing or a surgery, the health of livestock through a hard winter, a release from prison, or the arrival of a loved one after a long journey. This tapestry of miracles lined the walls of the refectory, each retablo about the size of a license plate, each describing the greatest miracle in one life’s journey. In this era of endless, ephemeral, often meaningless electronic communications—Tweets, Snapchats, Instagrams—I found the simplicity and permanence of the retablos profound.

On our last night in Mexico we met traveling ex-pats—a glamorous Chilean couple and an insouciant, long-haired Englishman who was cruising the Americas on a DR 650. The moon was full, and their plans involved a peyote ceremony. Ours involved more beer and cigarettes. The Englishman and his girlfriend had ridden the DR up the infamous back route to Real—a hellacious rough-hewn rock passageway not much wider than a sidewalk. It was not too hard, he said, as long as you wheelied most of your way up.

Stephen Thomas is a father, a writer, and a speech-language therapist in the public schools in Round Rock, Texas. He gets away from it all on a 2012 Suzuki V-Strom 650.

Stephen Thomas is a father, a writer, and a speech-language therapist in the public schools in Round Rock, Texas. He gets away from it all on a 2012 Suzuki V-Strom 650.

Read more …

Source link